flash fiction

Emma and Moonlight

I wrote this story a while ago. It was meant as a present for the daughter of a friend. The daughter was, and probably still is, a talented young artist. Unfortunately, her mother felt that the story was/is too sad. Subsequently, it was never delivered. It isn’t the first time I’ve had a story rejected and it probably won’t be the last, but I was disappointed at the time. Mothers know their children better than outsiders do, but on this occasion I think the mother was wrong — and a bit rude, if it comes to that. So, here’s the story. If you were an eleven year old, what would you think?

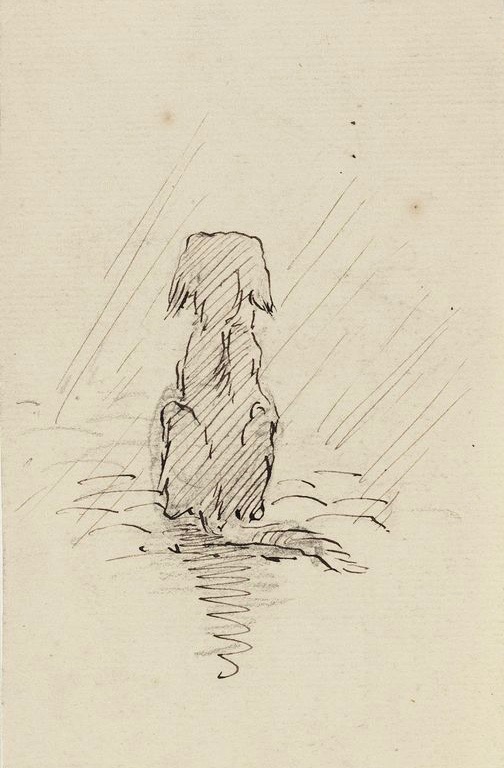

It has to be said that Moonlight was easier to see at night.

She was still there during the day, but she was harder to see.

Emma wondered about this, but only for a moment. Considering all the strange things that had happened around her over the past year, not being able to see her dog clearly during the day seemed like a small concern.

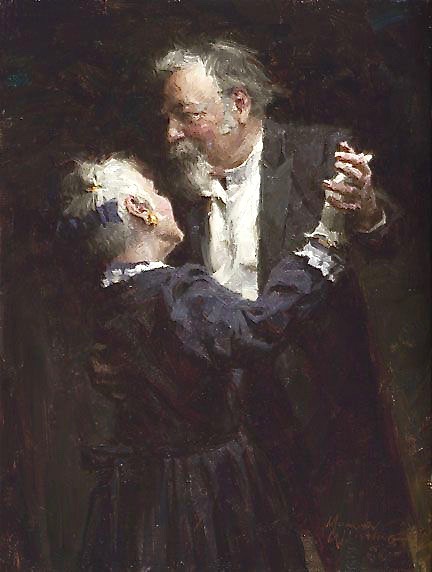

Emma’s second favourite part of her day was sitting on the old leather couch in her aunty and uncle’s lounge room watching a movie. She could have gone to her room and watched it on her computer — been alone with Moonlight, but she sensed that Moonlight enjoyed being with the grownups — hanging out. Considering Moonlight had defended her when she needed it most, Emma felt it was the least she could do.

Moonlight didn’t watch the screen, she watched Emma — head on her lap, sitting at her feet. Emma stroked her head and scratched behind her ears — Moonlight liked having her ears scratched, not because they were itchy, but because she knew this touch was full of love.

“Why do you do that Emma?” asked her aunty.

“No reason,” said Emma as she stopped stroking Moonlight.

Mrs Brown had been told not to make Emma feel like she was doing anything unusual. “Try not to notice when she does things — strange things. It’s all part of her healing process.”

Emma was slightly ashamed that she took advantage of the advice she overheard her psychologist give. Nevertheless, she took full advantage when it suited her, particularly around bedtime. Unfortunately, this only worked for a few weeks, and she learned not to overdo it — too precious an advantage to waste.

After a few months, the police stopped ‘dropping in for a chat’. They were hoping that Emma could remember more of that night, but there wasn’t any more to add to what she had already told them. Her mother told her to hide, and Emma was very good at hiding — she knew all the best places. She remembered the adults shouting — strange voices she didn’t recognise — Moonlight barking and growling, then silence. Emma stayed hidden until the policewoman in the white overalls found her. Two men were arrested at the Emergency department of the local hospital. Moonlight had inflicted severe wounds on them both — had driven them off before they could search the house — before they could hurt Emma.

The police said Moonlight was badly injured when they found her. She didn’t know who these people were so she tried to drive them away as well, but she was too wounded to put up much of a fight.

The policewoman in the white overalls told Emma that Moonlight had been taken to a Vet.

Moonlight was fine now. She came to Emma that first night — the night Emma rode in the police car to her uncle’s house. They turned the flashing blue lights on for her, but said they couldn’t turn the siren on, “It tends to wake people up, and people need their sleep.”

Emma didn’t sleep much this days.

In the beginning, it was strange to sleep in a new bed in a new house, but then she got used to the all the new things. Moonlight kept her company on those sleepless nights.

Emma didn’t have to go to school for several weeks, and when she did, it was a new school, and she had to start all over again — find new friends.

No one at her new school knew what had happened, although Emma sensed that her teacher knew something — they never talked about it.

Emma was the only girl at that school who was allowed to have her dog with her during the day. No one said why and she didn’t ask — she didn’t want them to send Moonlight away, so she didn’t bring it up.

Sometimes, Emma lost sight of Moonlight at school, but soon she would turn up with an old tennis ball or a bone and lay it at Emma’s feet.

“Not now Moonlight, I’ve got an essay to finish.”

Emma’s best friend, Josie, knew Moonlight, but sometimes the other girls would ask Emma who she was talking to.

“Don’t you talk to your dog?” Emma would ask.

Josie would usually change the subject and suggest that they all play a different game.

Emma didn’t catch the bus when it was time to go home from school because the long walk home with Moonlight was a highlight of her day.

Their usual route took them past Maccas, and if Emma had any pocket money left, she would buy a small ice cream cone and share it with Moonlight.

Moonlight loved ice cream almost as much as she loved Emma.

“You wait here Moonlight while I go and get an ice cream. Be a good girl.”

Sometimes Emma didn’t say why she was going into the shop because Moonlight would get very excited and spin around in circles at the thought of ice cream. It took her a long time to settle down and even when she was sitting, her bottom wiggled with delight. Even when she didn’t say the words, Moonlight knew what was about to happen — Moonlight was a bright dog — she knew stuff — what she didn’t know she could sense. She knew when Emma was happy or sad. She tried to lick away her tears, but Emma scolded her when she did. She wasn’t really mad at her and Moonlight knew it.

Mostly, Moonlight knew that her job was to stay close by because Emma needed her.

Moonlight knew that something was different after that night, but she didn’t waste time thinking about it — she had a job to do and a girl to whom she could give all her love — that was enough for her.

After ice cream, they would cut through the park and sometimes there were other dogs to play with. Some were hard to see in the daylight, and some weren’t, but dogs don’t worry about such things — they live in the moment.

After the park, there was Mrs Jenkins.

Mrs Jenkins was ancient, and she smelled like eucalyptus lollies. Moonlight liked lollies, and so did Emma.

Mrs Jenkins would be waiting for them, every day, standing at her front gate. When the weather was warm, they would all sit on her front verandah and drink milky tea. Moonlight would rest her head on Mrs Jenkins’ lap — she knew that Mrs Jenkins had a cat, but the warmth of a dog is unique. Moonlight knew that Mrs Jenkins was coming near to the end of her life. It had been a good life — full of wonder, but all of her friends were gone, and she was looking forward to seeing them again.

When Emma and Moonlight said their goodbyes, they walked the rest of the distance to their house, but they did it very slowly, not because they didn’t want to go home — they liked being there, but because they didn’t want the experience to end.

The days rolled into weeks and the weeks rolled into months, and as they did, Emma and moonlight settled into their new life — far away from their old home.

Emma’s aunty and uncle were kind, and their house was warm and comfortable, but it wasn’t their home — not really.

“You miss your mum and dad don’t you, Emma?” said her aunty. They had been watching a movie together, and the movie had gone into an annoying bit.

“I miss them every minute of every day, but Moonlight is still with me, and I don’t get too sad when she is around.”

“You do know that Moonlight died that night — defending you?”

“I know she was hurt, but she got better and came to me. I know she is a bit hard to see in the daylight, but she is always with me.”

Emma patted Moonlight and Moonlight licked her hand and went back to dreaming about walking home from Emma’s school and ice cream and playing in the park and Mrs Jenkins and her eucalypts lollies — life was good.

Wayback Wednesday: – A Pocket Full Of Thank You

©2017 Terry R Barca

I emptied the contents of my hand onto the time-worn pub table.

We inhabited this pub during happier times, and I guess we never broke the habit.

“What is that?” asked Harry, my former workmate. Harry and I once were warriors in the halls of finance. We slashed and burned our way to enormous profits — profits we saw very little of. That sounds like sour grapes, and I guess it is. We were paid very well and on at least one occasion, our Christmas bonus equalled the deposit on an expensive flat overlooking the river — I loved that view.

We thought we were invincible.

“That, my dear Harry is a pile of thank you,” I said with an air of mystery — I do a good mystery.

“Come again, young Charles?” Everyone at the firm called me young Charles. It made it easier, and even when older Charles left the company, I continued to be young Charles.

“It’s a moderately long story, do you want another pint before I begin?”

“Nah, I’ll make this one last.”

“You know that big old RAF greatcoat I used to wear?”

“The one that is hanging on the coat stand over there?”

“That’s the one.”

“I think I will get that drink. I get the feeling that this is going to be epic — you want one?”

“No, save your money. I’m pleasantly toasted, and it should last till lunchtime.”

In the old days, we didn’t have to worry about such things — money was always there, and just like everything else in life, we expected it to stay that way.

I watched Harry make his way to the bar. The girl behind the counter was new, and Harry fancied his chances — their conversation continued for some minutes. As Harry turned to come back to our table, I watched the young lady flash her eyes and run her fingers through her hair.

“I think I’m in there,” said Harry as he sat down. From what I saw, I’d say he probably was.

“It must be your Scotish charm.”

“They all want to know what is under the kilt.”

“You’re not wearing a kilt, Harry.”

“You know what I mean.”

“No, I don’t, but one day I’m sure you will enlighten me.”

We had both travelled a long way to come to London and make our fortune, and now we could not imagine going home with our tails between our legs. My hometown is Melbourne — on the other side of the world.

“So, if you’re sitting comfortably, I’ll begin.”

“Extremely comfy, thank you.”

“You know the park across from my flat?”

“Your old flat or the new one?”

“There is only a railway line across from my current abode.” I glared at him for reminding me of how far I had come down.

“On my days off —“

“Which you have a large number of nowadays,” interrupted Harry.

“Yes, thank you for reminding me. On my days off I would take my stale bread to the park and feed the birds. I wasn’t particular, anything with feathers got a fair share.”

“That was egalitarian of you,” said Harry.

“Thank you — one must maintain standards. So, this went on for many weeks when I discovered the substance you see before you, in the pocket of my greatcoat.”

Harry ran a cautious finger through the pile of what looked like very fine gravel.

“I didn’t pay it any attention at first. I assumed that it had fallen out of a tree, or I had brushed up against something as I walked through the park.”

“A reasonable assumption.”

“Agreed — then the amount of gravel got progressively larger until it reached the proportion you see before you.”

“So, what is it? I know you are dying to tell me.”

“I took a sample to a girl I was penetrating at the time, and between bouts of passion, I asked her if she knew what it was. This girl loves a mystery, so she leapt out of bed, stark naked, and put a couple of grains under her microscope.”

“You have to love a naked woman with a microscope.”

“My thoughts exactly. It turns out that she was not only good at all forms of coitus, but she was an excellent botanist as well.”

“Coitus beats Botanist though?”

“I agree, but on this occasion, she was both — result!”

“So?”

“Well, it turns out that they are the tops of tiny acorn like seeds — just the tops, and they are very sought after by the little birds that live in that park.”

“Little birds, is that their botanical name?”

“She did tell me, but in my defence, she was naked, and I was imagining all the things I could do to her before I had to go to work. Smoothest thighs you have ever seen and spectacular breasts.”

“Fair enough. Any man could forget a Latin name under such circumstances — you’re forgiven.”

“Anyway, these little birds spend hours looking for the caps off the seeds. They use them to make a sort of paste. They mix it with mud and sticks and make a very sturdy nest — a bit like adding gravel to cement. These tiny nut caps are their most treasured possession — they will fight other birds who try to move in on their supply.”

“And, they gave them to you?”

“Yes. I’m just as amazed as you are.”

“How do they manage to get them into your pocket without you noticing?”

“Good question. I guess it’s because I’m in a kind of meditative state — sitting by the lake, watching the birds. It was then, and still is, a kind of escape. But after the encounter with the naked Botanist, I watched them out of the corner of my eye. My coat pocket bends open just a bit as I sit and they come up from behind me and drop them in, one at a time.”

“Wow. It must take a while to deposit enough to make a pile like this.”

“I’m touched that they want to thank me. I guess they appreciate the food. Pickings must be very slim in the winter, especially if you have extra mouths to feed. Often, I would be the only one in the park, particularly on wet rainy days. That old greatcoat comes in handy. I turn up the collar and tuck in a scarf, and I’m warm as toast.”

“What about your head?”

“Large woollen fisherman’s hat.”

“Sorted.”

“I feel bad taking their most treasured possession, so I sneak back and sprinkle them under a nearby tree and hope that they don’t notice.”

“Boy, are you going to feel dumb if they turn out to be a cure for cancer.”

“I’ll risk it.”

We both went quiet for a while, the way that good friends can. We sat and drank our beer and thought back to those heady days when the world was ours for the taking.

Harry is the only friend I have left from those days. I remember the morning we turned up to work only to find the front doors chained and padlocked. I wondered how they were able to do that; then I remembered that our firm owned the whole building. The security guards were no help — I just wanted to get my stuff out of my desk — never happened — probably ended up in a skip.

As I remember, Harry and I walked to this pub and made a few calls before our work phones went silent. A couple of the directors had been fiddling the books. They knew that we were surviving on reputation and bugger all else. They packed a serious amount of cash into the company jet and headed for a warmer country. We should have seen it coming, but we were young, and thought we knew our worth — we were invincible.

The naked botanist stopped fucking me as soon as I could no longer squire her to important parties. The flat went after a few months — I wandered along in denial, thinking that the world needed my skill set, but whenever they read the name of the firm I had most recently been employed by, the answer was always the same — no room at the inn.

The blokes who came to throw me out of my flat were very good about it.

“Just take whatever you can carry mate, we’ll look the other way.”

Jolly decent of them really. It was the middle of the day, and they broke for lunch after changing the locks on my former flat.

“Can we buy you lunch young fella? Don’t take it too hard. We see a lot of this, especially nowadays. You can curl up and die, or you can come back stronger — it’s your choice.”

They were right, and I worked for them part-time for a while, but that life was not for me.

I’ve got a tiny flat with a view of a railway line, a warm coat and a good friend. My bank account will see me right for a few more months.

After that, who knows.

©2017 Terry R Barca

Wayback Wednesday: It Never Rains On Olga

First published 24/8/2019

Belgrave is a long way from where Madame Olga lives, but it is on a train line — the end of the line in fact, so she can attend the aptly named, ‘Big Dreams Market’.

Madam Olga has her favourite markets, and she always travels by train, sometimes having to change trains.

She carries all she needs on a trolley designed by Tony, her neighbour (more about him a bit later). The fold-up table is her largest burden, but Tony designed and built her a surface that folds up into a more manageable shape. Even so, she struggles with it if there are stairs or a steep incline.

The ‘Big Dreams Market’ is about half a kilometre from the train station in Belgrave, and all of it is uphill — one of the steepest hills in Melbourne. In the 1950s, Vauxhall cars tested their vehicles on Terry’s Avenue. Handbrakes and clutches were put to the test.

No one knows how old Madame Olga is and to be accurate, which is always important, she isn’t sure herself. Many moons and many men have passed since she was born, somewhere in eastern Europe. She came to Australia after the war, when we welcomed migrants (or New Australians, as we were taught to call them). These days our leaders are teaching us to distrust people from other lands — sadly, this is something that we take to readily.

Getting her belongings up the hill took Olga almost half an hour — folded up table and box of jars and an old wooden chair. She stopped many times. The tiny park that marks the spot where an original homestead once stood is a welcome rest stop. The big old house is gone and in its place is a large blacktop carpark, complete with white lines and the occasional tree. A supermarket chain bought the land from the homesteader’s descendants and the Anglican church back in the day when non-Catholic religions were dying.

Churches traditionally gained the high ground — closer to God, or were they just showing the people where the power is?

‘Big Dreams Market’ is held in the expansive grounds of the local Catholic church — they occupy the highest point on one side of the valley, and on the other side, the Catholics occupy the other peak with an all-girls high school.

There is a market very near to where Olga lives, but she cannot go there anymore — someone complained. She does not know who complained; she only knows that Mr Character, the secretary, told her that they didn’t have space for her anymore.

“You have lots of space. Your market is never full,” said Olga in reply.

Mr Character hesitated before answering. He wanted her to understand his predicament. He liked her very much, but the decisions of his organising committee bound him.

“You’re right; I should have been honest with you. You are too successful, too different and there are people in this world who are afraid of ‘different’, and more to the point, they are afraid of those who do not seem to care what others think of them. That’s you Madame Olga, and I’m sorry. I love your elixir, your ‘Imagine’. I hope you will sell me more when I run out?”

“I have lived a long time, and I understand small minds. I will go,” said Olga. She wasn’t exactly sad, but this market was so convenient, so close to home.

The first monthly market after Olga had been excluded, it rained.

People remarked that it had been a very long time since it had rained on market day, and that was all that was said.

There were other markets, of course, but when you do not drive, there are other considerations. Olga could drive, and she had driven, but not since her Vance had died. She didn’t feel confident without him by her side.

The tiny market at Laburnam was her favourite. It is right next to the station, tucked into a small carpark near a group of shops. Very quiet except for the occasional passing train, way up high.

Box Hill market is her most lucrative. It’s enormous, and the largely immigrant population come from parts of the world where strange things are commonplace, so she does not seem out of place.

“You make good stuff,” said the old lady of Chinese descent, “my grandma used to make potions — make you fall in love, whether you like it or not.” The old lady laughed, and Olga smiled as well.

“Love is good, but potions wear off,” said Olga.

“Not the way my grandmother made them. How do you think I got to be born? My father not have a chance.” The old lady laughed again and moved off unsteadily with her small glass jar with the gold top.

A bored teenage girl was working her way up and down the aisles giving out leaflets when someone told her to stop. An argument broke out.

“I’m just doing what my dad told me to do,” she said.

“If you want to hand out leaflets rent a stall like everyone else,” said the tall man with the strange haircut. The upset, previously bored, teenager disappeared only to reappear with a short man with very little hair. A new conversation broke out with lots of arm-waving, but the man with the bad haircut stood his ground and told them to leave. They did, but not before throwing the remaining leaflets up in the air.

They rained down like A5 pieces of snow, fluttering on the gentle breeze. Small children cheered, and adults brushed the leaflets from their clothes and bags and prams. A particularly chubby baby sucked furiously on a leaflet that her distracted mother had missed.

After this moment of distraction, shoppers and stallholders returned to their duties.

Big Dreams Market, every last Sunday of the month, St Somebodyorother’s church grounds, Belgrave. 10 am till 4 pm. Come, and make your dreams come true.

Olga folded the flyer and put it in her pocket. Something told her that this knowledge might come in handy.

Olga’s first ‘Big Dreams Market’ was held in May and the established stallholders remarked on her lack of an awning.

“This is The Hills luv. If it’s gonna rain anywhere, it will rain here first. You are gonna need a cover,” said the man who was setting up his wife’s pottery stall. He seemed like an organised bloke. He knew where everything was, and he laid it out, ‘just so’.

Olga looked at the sky. The clouds were leaden, threatening, full of moisture.

“It not rain while market is running,” she said.

The pottery husband laughed.

“You a bit of a soothsayer luv?” Olga didn’t answer. She unfolded her table, laid out her embroidered table cloth and stacked up the tiny jars. She placed the old wooden chair very close to the edge of the pottery stall. The man looked at her with a look that said, “Don’t let that chair venture on to my wife’s area.”

Despite the threatening weather, there was a continuous flow of market shoppers. Small children and young couples with and without prams. Older couples in colourful scarves and giggling teenagers trying not to look as though they were checking each other out.

Customers react to Olga’s Elixer in many different ways, but on this day, there was a lot of ‘flying’.

Late in the day, Olga was distracted by a loud bang, and as she turned, she knocked over the jar of toothpicks. It was almost empty, but the remaining toothpicks spilled onto the ground. Olga groaned. Getting down that far was very difficult for her and picking up the tiny shards of wood was a lot to expect of her ancient fingers.

“I’ll pick them up for you lady,” said a boy of some twelve years. His jeans were clean but well worn, and his jumper was a hand knit. His dark hair was long and brushed back.

“Thank you, young man,” said Olga.

The boy quickly retrieved the picks and the unbroken jar. He placed them on the table and smiled at Olga.

“Your mother loves you very much, but she is also sad. This will pass, but you need to be patient and hug her a lot. Don’t worry if she is quiet. She is not upset with you. Grief shows itself in different ways. I know you feel it too, but you are able to smile,” said Olga and tears appeared in the boy’s eyes.

“I try to make her happy, but nothing works,” said the boy, brushing something away from his eye.

“It not your job to make her happy. It your job to love her, no matter what. Do not be afraid. Let her lean on you when she needs to. And you lean on her as well, when you need to. She won’t break, “said Olga.

The boy gave half a wave, brushed something else from his eye took a few steps back and moved away.

“You were right,” said the pottery husband as they packed up, “it didn’t rain.”

“It is good to listen to Olga when she speak of weather,” said Olga.

The pottery husband laughed. “How did you go today?”

“Well,” said Olga, not wanting to give too much away, “and your wife, she sell much?”

“Never as much as she would like but enough to buy more clay and stuff.”

With everything securely strapped into place (Tony taught her how to tie especially strong knots), Olga faced the daunting task of getting down the hill to the station.

She put the trolley behind her after having it nearly drag her down the hill.

Her legs and her back ached by the time she reached the ramp that led to the station. She must have looked a sight as she staggered down the hill. Passengers in passing cars staring at her as though she might suddenly break into a gallop and topple down the steep incline.

Finally, she got to step onto the waiting train, where she made herself comfortable, catching her breath.

The journey home was uneventful with the occasional passenger having to step around her trolley.

Olga was satisfied with her first day at ‘Big Dreams’.

As the train pulled out of the station, she noticed the man who had been one of her customers. He was with his large family, only now he was with an old dog — the dog she had seen with a small boy. The dog’s lead was a piece of string. The dog looked happy, and so did the older man, but it’s hard to judge happiness from a rapidly accelerating train.

Wayback Wednesday: PRECIOUS and the LIBRARIAN

Originally published March 11 2017

As a general rule, librarians consider dogs to be something that are best kept on the street side of the door.

Precious was the exception.

The library staff at the East Side Library liked their job. It wasn’t well paid, but the hours were reasonable.

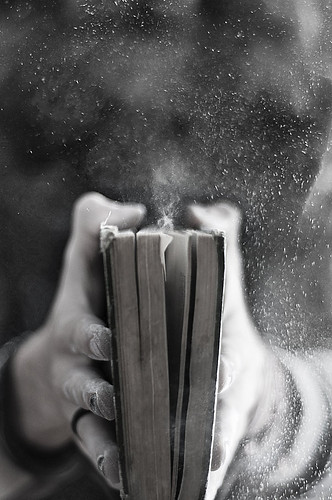

The south-east corner of the building had been damaged during the war — one of the many air-raids. The town council didn’t have the funds to carry out the repairs so that part of the building had been inaccessible to the public for many years. The government engineers had reinforced the structure with massive beams of oak — one of the few things that we had in abundance after the war. So the building was safe, but there were no plans to restore it, ‘books come way down the list’, was the official reply when the head librarian sent in her yearly formal request for building repairs. It irked her that the countries that had been defeated seemed to be benefiting from reconstruction while her library lay wounded all these years after victory.

Because the damaged part of the building was not considered to be officially part of the library, Jane Delbridge did not have a problem with Terry and Precious enjoying its privacy and comfort. It was cold in this section of the building, but not as cold as sitting out on the footpath in the snow — even if she was wearing the sleeve of one of Terry’s old army jumpers as a coat.

Mrs Delbridge lost her husband in North Africa during the war, and she looked upon ex-soldiers with warmth and respect. Terry and Precious went to the library every Monday and Thursday — regular as clockwork. Mrs Delbridge left the side door open so Terry and Precious could enter without drawing attention to themselves. The door frame was warped from the explosion, so it did not open easily. Terry thought about repairing it but decided against it — too obvious.

The room that they shared was partially open to the air, but the roof was still intact, and the hole was not on the ‘bad weather side’ of the building, so water was rarely a problem. None-the-less, time was eating away at the building, and Mrs Delbridge was rightly worried that the council would use the deteriorating condition of the building to justify pulling it down. It stood on prime real estate, and the council could use the resultant flood of money for desperately needed projects. Fortunately, many of the library’s customers were influential members of the community, and they made it clear that the building was off-limits.

The room with a view as Terry called it, had an old table and a dusty couch that had been rescued from a building that was being demolished. The hole in the wall let in more than enough light to read by. Precious claimed one end of the couch while Terry sat and read at the other end. Cups of tea would mysteriously appear from time to time, and the rings of countless cups were imprinted into the unpolished surface of the small table.

Choosing a book was the most difficult task. The library was well stocked from before the war, and they had inherited books from libraries that were more unlucky. The library staff spent many hours repairing damaged books because they knew that just like money for building repairs, money for new books was way down the list.

Terry enjoyed detective stories, and Mrs Delbridge had introduced him to Chandler and Hamett. She also headed him towards Green and Maugham. She was looking after his mind. He had been spared, and now she would show him the wonders of beautiful words.

Sometimes, just for the enjoyment of it, Terry would read to Precious. She seemed to enjoy A Moon and Sixpence, but he wasn’t sure why. She didn’t like Dickens, which was a shame, but she did like Conan Doyle. Terry did all the voices and tried to make it as exciting as possible. He worried that Precious might get bored waiting for him each night. The truth was that Precious didn’t need to be entertained. All she needed was to be close by — close to Terry. That was enough for her.

It’s important to know how much is enough.

This story is an extract from SECRETS KEPT, a novel by Terry R Barca

Flashback Thursday: BEEN AWAY SUCH A LONG TIME

First published April 10th 2019